Travis Letter From The Alamo

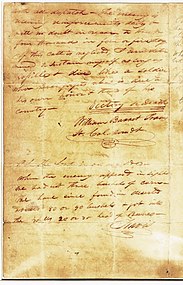

The 2nd page of the letter

To the People of Texas & All Americans in the Globe is an open letter written on February 24, 1836, by William B. Travis, commander of the Texian forces at the Battle of the Alamo, to settlers in Mexican Texas. The letter is renowned every bit a "annunciation of disobedience"[ane] and a "masterpiece of American patriotism",[2] and forms office of the history education of Texas schoolchildren.[iii]

On February 23, the Alamo Mission in San Antonio, Texas had been besieged past Mexican forces led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna. Fearing that his modest group of men could not withstand an assault, Travis wrote this letter seeking reinforcements and supplies from supporters. The letter of the alphabet closes with Travis's vow of "Victory or Death!", an emotion which has been both praised and derided by historians.

The letter was initially entrusted to courier Albert Martin, who carried it to the boondocks of Gonzales some seventy miles away. Martin added several postscripts to encourage men to reinforce the Alamo, and then handed the letter to Launcelot Smithers. Smithers added his own postscript and delivered the letter to its intended destination, San Felipe de Austin. Local publishers printed over 700 copies of the letter. Information technology besides appeared in the two primary Texas newspapers and was eventually printed throughout the Usa and Europe. Partially in response to the letter, men from throughout Texas and the United states began to gather in Gonzales. Betwixt 32 and 90 of them reached the Alamo before information technology barbarous; the residuum formed the nucleus of the regular army which eventually defeated Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto.

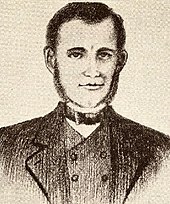

Following the end of the Texas Revolution, the original letter was delivered to Travis's family in Alabama, and in 1893, 1 of his descendants sold it to the Land of Texas for $85 ($2,564 today).[4] For many decades it was displayed at the Texas State Library; the original letter was and so placed in a nighttime space for conservation purposes, and the display is now an exact facsimile. Information technology is busy by a portrait of Travis.

Background [edit]

The Mexican Constitution of 1824 liberalized the country's immigration policies, assuasive foreigners to settle in border regions such as Mexican Texas. People flocked to the area; an 1834 census estimated the Texas population at vii,800 Mexicans and 30,000 English-speaking people primarily from the United States.[five] [Notation i] Amidst the immigrants was William Barret Travis, an Alabama native who had variously worked every bit a teacher, a newspaper publisher, and a lawyer.[vi] An avid reader, Travis often devoured a novel in a single day. His taste ran primarily to romantic gamble and history, peculiarly the novels of Sir Walter Scott and Benjamin Disraeli and the historical works of Herodotus.[7] Historians take speculated that Travis's choice of reading material may have affected his behavior[7]—Travis was known for his melodramatic ways.[8]

In May 1831, Travis opened a law office in Anahuac, Texas.[ix] Almost immediately, he and his police force partner, Patrick Jack, clashed with the local armed forces commander, Juan Davis Bradburn. Their subsequent actions were instrumental in causing the May 1832 Anahuac Disturbances.[ix] According to historian William C. Davis, Bradburn "overreacted and fabricated heroes of two local malcontents whose actions their own people otherwise had not been much inclined to sanction".[10] Bradburn was forced to resign his mail service and abscond Texas.[ix]

The Anahuac Disturbances coincided with a Mexican civil war. Texians aligned themselves with proponents of federalism advocating a stronger role for land governments, in opposition to a centralized government that prepare most policies at the national level. The federalists prevailed, and their favored general, Antonio López de Santa Anna, was elected president. In 1835, Santa Anna began consolidating ability; in response federalists launched armed rebellion in several Mexican states. Travis, an ardent foe of centralism, led an assail on Anahuac in June 1835 and forced the Mexican garrison to surrender. Many Texas settlers thought Travis'due south activeness was imprudent, and he was forced to apologize. Although the Mexican authorities issued a warrant for his arrest, local authorities did not enforce information technology.[11]

Texians became increasingly discontented with the government equally Santa Anna positioned himself every bit a dictator. In Oct, the Texas Revolution began and delegates appointed a provisional government. Travis was commissioned lieutenant colonel in the new regular army and asked to raise a cavalry company.[12] He participated in the siege of Béxar, where he proved to be "an impulsive, occasionally insubordinate, officer".[13]

By the stop of 1835, Texians had expelled all Mexican troops from Texas. Believing the war ended, many Texians resigned from the army and returned home.[14] In January, the provisional government essentially collapsed; despite a lack of say-so for any co-operative of government to interfere with other branches, the legislature impeached Governor Henry Smith, who in plough disbanded the legislature. No one in Texas was entirely sure who was in charge.[15]

Even equally Texian governmental say-so declined, rumors flew that Santa Anna would personally atomic number 82 an invasion of Texas to quell the rebellion.[16] Despite this news, Texian army forcefulness connected to dwindle. Texas settlers were divided on whether they were fighting for independence or a return to a federalist government in Mexico. The confusion caused many settlers to remain at home or to return home.[3] Fewer than 100 Texian soldiers remained garrisoned at the Alamo Mission in San Antonio de Béxar (at present San Antonio, Texas). Their commander, James C. Neill, feared that his modest force would be unable to withstand an assault by the Mexican troops.[17] In response to Neill's repeated requests for reinforcements, Governor Smith assigned Travis and 30 men to the Alamo; they arrived on February 3.[18] Most of the Texians, including Travis, believed that whatsoever Mexican invasion was months away.[nineteen]

Composition of the letter [edit]

Travis assumed command of the Alamo garrison on February 11, when Neill was granted a furlough.[twenty] [Note 2] On Feb 23, Santa Anna arrived in Béxar at the caput of approximately 1500 Mexican troops.[21] The 150 Texian soldiers were unprepared for this evolution.[19] [22] As they rushed to the Alamo, Texians quickly herded cattle into the complex and scrounged for food in nearby houses.[23] [Annotation 3] The Mexican army initiated a siege of the Alamo and raised a claret-red flag signalling no quarter. Travis responded with a blast from the Alamo's largest cannon.[21]

The showtime night of the siege was largely tranquillity. The post-obit afternoon, Mexican artillery began firing on the Alamo. Mexican Colonel Juan Almonte wrote in his diary that the bombardment dismounted ii of the Alamo's guns, including the massive xviii-pounder cannon. The Texians quickly returned both weapons to service.[24] Soon after, Travis wrote an open letter pleading for reinforcements from "the people of Texas & All Americans in the World".

To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World:

Fellow citizens & compatriots—I am besieged, by a one thousand or more than of the Mexicans under Santa Anna—I have sustained a continual Bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have non lost a man. The enemy has demanded a give up at discretion, otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken—I take answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag withal waves proudly from the walls. I shall never give up or retreat. And then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American graphic symbol, to come up to our assist, with all dispatch—The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no incertitude increase to three or four thousand in iv or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long every bit possible & dice similar a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own accolade & that of his country— Victory or Expiry .

William Barret Travis

Lt. Col. comdt

P.Southward. The Lord is on our side—When the enemy appeared in sight we had not three bushels of corn—We have since found in deserted houses eighty or ninety bushels & got into the walls xx or thirty head of Beeves.

Travis[25] [Note 4]

Distribution [edit]

Both Albert Martin and Launcelot Smithers added postscripts to the back of Travis'south alphabetic character. The two postscripts are visible in this scan of the document.

Travis entrusted the letter to courier Albert Martin, who rode through the nighttime to comprehend the seventy miles (110 km) to the closest boondocks, Gonzales, as quickly as possible.[26] During his journey, Martin added two postscripts. The first relayed Martin's fear that the Mexican ground forces had already attacked the Alamo[Annotation 5] and ended "Hurry on all the men y'all can in haste".[27] The 2nd postscript is more difficult to read, equally the letter was later folded along one line of text. The paper has since partially frayed forth the fold, obliterating several words.[28] The gist of the bulletin, all the same, is that the men at the Alamo were "determined to do or die", and Martin intended to gather reinforcements and return as rapidly as possible.[27]

In Gonzales, Martin turned the letter over to Launcelot Smithers.[29] When the Mexican ground forces arrived in Béxar, Smithers had immediately ready out for Gonzales. Travis may take sent him as an official courier, or he may have journeyed in that location on his ain to warn the townspeople.[30] Smithers added his ain message under Martin's, encouraging men to get together in Gonzales to go to the relief of the Texians at the Alamo.[27]

Before parting Gonzales, Smithers gave a letter of the alphabet to Andrew Ponton, the alcalde (or mayor) of the town. This second letter may have actually been the reason Smithers travelled to Gonzales, or information technology might accept been a paraphrased version of the letter Martin had delivered.[31] The copy read:

To All the Inhabitants of Texas:

In a few words there is 2000 Mexican soldiers in Bexar, and 150 Americans in the Alamo. Sesma is at the head of them, and from best accounts that tin can be obtained, they intend to show no quarter. If every man cannot plough out to a man every human being in the Alamo will be murdered.

They have non more than than 8 or x days provisions. They say they will defend it or die on the ground. Provisions, armament and Men, or suffer your men to be murdered in the Fort. If you practice not plow out Texas is gone. I left Bexar on the 23rd at four P.M. Past order of

W.V. [sic] Travis

L. Smithers[31] [Note half-dozen]

Ponton sent the Smithers copy of the letter to Colonel Henry Raguet, the commander of the Committee of Vigilance and Safety in Nacogdoches. Raguet kept the letter he received and sent a copy, with his additional comments, to Dr. John Sibley, the chairman of the Committee of Vigilance and Safety for Texas Affairs in Natchitoches, Louisiana.[32]

Smithers rode hard and delivered Travis's alphabetic character to San Felipe de Austin in fewer than forty hours. In a hurriedly organized meeting, town leaders passed a serial of resolutions pledging assistance to the Alamo defenders. The results of the meeting were printed in a broadsheet alongside a reproduction of Travis's alphabetic character. After distributing all 200 copies of their initial impress run, newspaper publishers Joseph Baker and Thomas Borden made at to the lowest degree four other reproductions of the letter, resulting in more than than 500 additional copies.[32] [33] Their terminal printing included a message from Governor Henry Smith urging the colonists "to fly to the aid of your besieged countrymen and non permit them to exist massacred by a mercenary foe. ... The phone call is upon ALL who are able to bear arms, to rally without one moment'southward delay, or in xv days the middle of Texas will be the seat of war."[34] On March ii, the alphabetic character was printed in the Texas Republican. Information technology appeared in the other major Texas newspaper, the Telegraph and Texas Annals, three days afterwards.[33] The letter was somewhen reprinted throughout the The states and much of Europe.[24]

Texan response [edit]

This letter was one of several that Travis sent during the siege of the Alamo. Each carried a similar bulletin—the Mexican army had invaded Texas, the Alamo was surrounded, and the Texans needed more men and ammunition to wage a successful defence.[35] No aid was forthcoming from the Texas government. By this indicate infighting had rendered the provisional government completely ineffective, and delegates convened on March 1 at the Convention of 1836 to create a new government. Most of the delegates believed that Travis exaggerated the difficulties he faced.[36]

Many Texas residents disagreed with the convention'southward perception. Every bit the message spread across Texas, settlers left their homes and assembled in Gonzales, where Colonel James Fannin was due to go far with the remaining Texan Regular army troops.[37] [Note 7] On February 27 one group of reinforcements impatiently set out on their own; as a effect 32 additional Texans entered the Alamo.[38] [39] Research by historian Thomas Ricks Lindley indicates that an boosted 50 or 60 men reinforced the Alamo on March 4.[twoscore]

Near all of the Texans were killed at the Battle of the Alamo when the Mexican army attacked on March six; Travis was likely the beginning to dice.[41] [42] Unaware that the Alamo had fallen, reinforcements continued to get together; over 400 Texans were waiting in Gonzales when news of the Texan defeat reached the town on March eleven.[43] Before that twenty-four hour period, General Sam Houston, newly reappointed commander of the Texan Ground forces, had arrived in Gonzales. On hearing of the Alamo's fall, Houston took command of the assembled volunteers. The following month, this hastily organized army defeated Santa Anna at the Boxing of San Jacinto, ending the Texas Revolution.[44]

This letter may have influenced the election of David Chiliad. Burnet every bit acting president of the new Republic of Texas. After reading 1 of the broadsheet versions of the letter, Burnet rushed to join Travis at the Alamo. Afterward stopping at Washington-on-the-Brazos to recruit reinforcements from the men assembled at the Convention of 1836, Burnet became so "inspired past their deliberations" that he remained as a company.[45] The convention declared independence from Mexico on March 2, but delegates feared for the safety of the new country's officers. Speaking privately with many of the delegates, Burnet professed his willingness to serve equally president of a new republic, even if that made him a target of Santa Anna.[45] The most pop delegates were absent from the convention on other business for the war attempt. In the absenteeism of interest in the position from most of those remaining, Burnet was nominated for president and defeated the only other candidate, Samuel Carson, by a 29–23 margin.[46]

Preservation [edit]

Subsequently the Texas Revolution concluded, the original draft of the letter of the alphabet was given to Travis's family in Alabama. Several prominent Texians are known to take visited Travis's estranged wife shortly after the hostilities concluded, but historians are unsure which of these men might have delivered the letter. Travis's daughter Susan (anile five at the time of his decease) passed the letter down to her descendants; it eventually reached her great-grandson, John Yard. Davidson. In Feb 1891, Davidson lent the letter to the Texas Department of Agriculture, Insurance, Statistics, and History.[47] 2 years after, Davidson offered to sell the letter to the land of Texas for $250 ($vii,540 today)[4]. This represented half of the annual sum allocated for collecting historical manuscripts, and the state was hesitant to agree. After negotiations, Davidson agreed to accept $85 ($2,564 today)[4] for the letter, and on May 29 it officially passed into state buying.[47]

For many decades, the letter was publicly displayed, usually in a locked drinking glass instance with other manuscripts and artifacts from the Texas Revolution. At times, it was bundled alongside the Travis family unit Bible and a copy of Travis'due south will.[47] In 1909, the letter was moved to the Texas State Library and has since left that edifice simply twice;[47] it was amongst 143 documents lent to the Committee on Historical Exhibits for the Texas Centennial Exposition in 1936, and it returned briefly to the site of the exposition in 1986.[48] The original letter is no longer on permanent display. In its place is, in the words of Michael Green, former reference archivist for the Texas State Library Archives Division, "an exacting, one-of-a-kind facsimile".[48] Direct over its brandish example is a portrait of Travis.[48]

Iv copies of the original broadsides are known to survive. 1 was placed for auction in 2004, where it was predicted to achieve a cost of over $250,000.[49]

Return to the Alamo [edit]

In October 2012, the Texas General State Office announced plans to display the famous Travis Letter in the Alamo from February 23 to March 7, 2013. This marked the beginning time the iconic letter has returned to the Alamo since information technology was written by Travis. The display was complimentary and open up to the general public.[50]

Reception [edit]

Travis' letter is regarded as "the well-nigh famous document in Texas history",[25] just its widespread distribution immune an impact outside the relatively isolated settlements in Texas. Historians place the alphabetic character in a broader context, "as one of the masterpieces of American patriotism"[ii] or even "one of the greatest declarations of defiance in the English language".[1] It is rare to see a book about the Alamo or the Texas Revolution which does not quote the letter, either in full or part.[28] The letter likewise appears in full in most Texas history textbooks geared towards simple and eye school children.[3] The postscripts, however, take rarely been printed.[28] Despite its asserted impact, minimal scholarship exists on the letter itself.[51]

Travis concluded his letter with the words "Victory or Death", followed by his signature and title (Lt.Col. comdt). The give-and-take choice is patterned subsequently Patrick Henry'south weep "Liberty or Expiry!"

Almost from the moment of his arrival in Texas, Travis had attempted to influence the war calendar in Texas.[3] Every bit he realized the magnitude of the opposition he faced at the Alamo, the tone of Travis's writings shifted from perfunctory reports to the conditional government to more eloquent messages aimed at a wider audience.[52] With limited time and opportunity to sway people to his way of thinking, Travis'south success, and perhaps his very survival, would depend on his ability to "emotionally motion the people".[53] His previous work every bit a journalist probable gave him a adept understanding of the blazon of language that would most resonate with his intended audition.[54] Travis used this detail letter of the alphabet non only as a means to publicize his firsthand demand for reinforcements and supplies, but likewise to shape the contend within Texas past offering "a well-crafted provocation" that might incite others to have upwards arms.[iii] He chose "unambiguous and defiant" linguistic communication,[55] resulting in a "very powerful" message.[56] The letter represented an unofficial declaration of independence for Texas.[57] [Annotation 8] Its word usage evoked the American Revolution and Patrick Henry'southward famed weep of "Liberty or Decease!"[58]

Critics have derided the letter for its emotionalism, noting that it appears to prove "a preoccupation with romance and chivalry" not uncommon to fans of Sir Walter Scott.[6] In detail, they bespeak to Travis's asserted determination to sacrifice his ain life for a lost crusade.[51]

Notes [edit]

- ^ As a comparison, in 1825, the Texas population comprised approximately 3,500 people of Mexican descent, with few English-speaking settlers. (Edmondson (2000), p. 75.)

- ^ The volunteers already gathered in the Alamo did not take the appointment of Travis, a regular army officer. They instead elected James Bowie every bit their commander. Bowie and Travis shared command until the morning of February 24, when Bowie collapsed from illness. At that bespeak, Travis causeless sole command. (Hardin (1994), pp. 117–xx.)

- ^ Many residents of San Antonio de Béxar had fled when they learned that the Mexican Army was approaching, leaving near of the homes empty. (Edmondson (2000), p. 301.)

- ^ "I shall never give up or retreat" was underlined once, while "Victory or Death" was underlined thrice. (Dark-green (1988), p. 492.)

- ^ Martin had heard cannon fire every bit he left the Alamo. (Green (1988), p. 493.)

- ^ Many at the Alamo believed that Full general Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma was commanding the Mexican troops, and that Santa Anna would get in soon with farther reinforcements. (Edmondson (2000), p. 349.)

- ^ Fannin aborted his reinforcement mission on Feb 27 and returned to Goliad. (Edmondson (2000), pp. 324, 328.) He and many of his men were executed past Mexican troops during the Goliad Massacre in late March.

- ^ The Convention of 1836 did non officially declare independence for Texas until March 2. Alamo defenders were unaware of this development.

References [edit]

- ^ a b Stanley, Dick (March 1, 2000), "Remembering Our Roots; As Independence Day nears, some may try to forget the Alamo.", The Austin American-Statesman, Austin, TX, p. B1

- ^ a b Petite (1998), p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e McEnteer (2004), p. sixteen.

- ^ a b c 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Toll Index for Employ as a Deflator of Coin Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Utilise as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the U.s. (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Alphabetize (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Manchaca (2001), pp. 172, 201.

- ^ a b Greenish (1988), p. 484.

- ^ a b Green (1988), p. 486.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 156.

- ^ a b c Green (1988), p. 485.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 86.

- ^ Todish et al. (1988), p. 6.

- ^ Green (1988), p. 489.

- ^ Green (1988), p. 488.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 91.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 31.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 98.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 109.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 117.

- ^ a b Hardin (1994), p. 121.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 32.

- ^ a b Todish et al. (1998), p. 40.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 299.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 301.

- ^ a b Todish et al. (1998), p. 42.

- ^ a b Green (1988), p. 492.

- ^ Green (1988), p. 499.

- ^ a b c Green (1988), p. 493.

- ^ a b c Green (1988), p. 498.

- ^ Petite (1998), p. 89.

- ^ Greenish (1988), p. 500.

- ^ a b Green (1988), pp. 503–four.

- ^ a b Green (1988), p. 504.

- ^ a b Light-green (1988), p. 505.

- ^ Petite (1998), p. 90.

- ^ Lord (1961), p. 111.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 149.

- ^ Lindley (2003), pp. 125–30.

- ^ Lindley (2003), p. 130.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 340.

- ^ Lindley (2003), p. 142.

- ^ Todish et al. (1998), p. 52.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 407.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 375.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), pp. 375, 378–86.

- ^ a b Davis (1982), p. 37.

- ^ Davis (1982), p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Green (1988), p. 507.

- ^ a b c Greenish (1988), p. 508.

- ^ Dorsett, Amy (Dec 2, 2004), "Remember the letters!", San Antonio Limited-News , retrieved 2009-01-28

- ^ Huddleston, Scott (October 25, 2012). "Alamo volition get alphabetic character past Travis". San Antonio Limited-News. San Antonio, TX. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Green (1988), p. 483.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 217.

- ^ Lindley (2003), p. 97.

- ^ Davis (2006), p. 218.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 126.

- ^ quotation is from Danini, Carmina (February 24, 2001), "Defiant Travis letter still stirs", San Antonio Limited-News, p. 1B . A similar sentiment is expressed by Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 129.

- ^ Roberts and Olson (2001), p. 129.

- ^ Schoelwer (1985), p. 135.

Sources [edit]

- Davis, Joe Tom (1982). Legendary Texians. Vol. i. Austin, TX: Eakin Press. ISBN0-89015-336-i.

- Davis, William C. (2006). Lone Star Ascension. College Station, TX: Texas A&Thou Academy Press. ISBN978-i-58544-532-five. originally published 2004 past New York: Free Printing

- Edmondson, J.R. (2000). The Alamo Story-From History to Current Conflicts. Plano, TX: Democracy of Texas Press. ISBN1-55622-678-0.

- Green, Michael R. (ane April 1988). "To the People of Texas and All the Americans in the World". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Texas State Historical Association. 91 (4): 483–508. JSTOR 30240052.

- Hardin, Stephen L. (1994). Texian Iliad. Austin, TX: University of Texas Printing. ISBN0-292-73086-i.

- Lindley, Thomas Ricks (2003). Alamo Traces: New Evidence and New Conclusions. Lanham, MD: Republic of Texas Printing. ISBNi-55622-983-6.

- Manchaca, Martha (2001). Recovering History, Constructing Race: The Indian, Black, and White Roots of Mexican Americans. The Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Series in Latin American and Latino Art and Culture. Austin, TX: University of Texas Printing. ISBN0-292-75253-ix.

- McEnteer, James (2004). Deep in the Heart: The Texas Trend in American Politics . Portsmouth, NH: Praeger Publishers. ISBN978-0-275-98306-2.

- Petite, Mary Deborah (1999). 1836 Facts about the Alamo and the Texas State of war for Independence. Mason City, IA: Savas Publishing Company. ISBN1-882810-35-X.

- Roberts, Randy; Olson, James Southward. (2001). A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory. The Free Press. ISBN0-684-83544-4.

- Schoelwer, Susan Prendergast (1985). Alamo Images: Irresolute Perceptions of a Texas Experience. Dallas, TX: The DeGlolyer Library and Southern Methodist University Printing. ISBN0-87074-213-2.

- Todish, Timothy J.; Todish, Terry; Spring, Ted (1998). Alamo Sourcebook, 1836: A Comprehensive Guide to the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: Eakin Press. ISBN978-1-57168-152-2.

External links [edit]

- Travis' Letter of the alphabet at the Texas State Library

Travis Letter From The Alamo,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/To_the_People_of_Texas_%26_All_Americans_in_the_World

Posted by: davidsonnoby1984.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Travis Letter From The Alamo"

Post a Comment